Ancient Artistry

Paleoart—the artistic representation of prehistoric life—has long served as a bridge between science and imagination. From the first crude depictions of Ice Age animals on cave walls to the stunningly realistic digital reconstructions of today, paleoart has continually evolved alongside scientific discoveries. This article explores the fascinating history of paleoart, its influence on public perception, and how advances in paleontology have shaped its accuracy over time.

Cave Creations

Before the formal study of paleontology, ancient humans were already depicting the natural world around them. Some of the earliest known depictions of prehistoric animals come from cave art such as those found in France’s Lascaux Cave and Chauvet Cave, dating back more than 30,000 years. These paintings, while not necessarily intended as scientific reconstructions, provide invaluable glimpses into how early humans perceived their environment.

However, these representations were limited to creatures that coexisted with humans. Extinct creatures such as dinosaurs would remain largely unknown until much later, with their depictions emerging only after the scientific discovery of their fossils.

Rock Art Artisans

Prehistoric art provides a vital glimpse into the ways early humans depicted their world, offering insight into their experiences and environments. As evidenced by numerous ancient works, early humans created art that often reflected their surroundings—be it through cave paintings, rock carvings, or sculptures. This artistic expression, which emerged during the Upper Paleolithic period (20,000–8,000 BCE), likely served both practical and spiritual purposes. Early human art often depicted animals, hunting scenes, or symbolic motifs, highlighting their relationships with the natural world. The artworks, particularly in caves across Europe, display advanced understanding of light, shadow, and perspective, showcasing the human desire to record and interpret the environment.

The rock art of Oregon, specifically, provides a fascinating chapter in the history of prehistoric art in North America. The Bradshaw Foundation highlights significant rock art sites in the Oregon Territory, an area rich with petroglyphs and pictographs that reveal much about the lives of indigenous peoples. The Pacific Coast, Klamath River, Columbia River Drainage, and Great Basin areas all feature unique rock art styles, with some sites dating back thousands of years. These works not only document the natural world but also offer insights into cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and territorial significance. D. Russel Micnhimer and LeeAnn Johnston’s extensive photographic and archival research has contributed significantly to understanding these art forms, preserving a visual record of Oregon’s prehistoric art that serves both academic and preservationist purposes.

Thus, from the ancient caves of Europe to the petroglyphs of Oregon, human art has long been a tool for recording and interpreting the environment, illustrating the timeless connection between people and the landscapes they inhabit.

The Birth of Scientific Paleoart

The 19th century saw a surge in fossil discoveries, prompting the first attempts to visualize extinct creatures. One of the earliest known paleoartists, Henry De la Beche, created Duria Antiquior (1830), a watercolor painting based on fossil evidence from England’s Jurassic Coast. This marked the beginning of scientifically informed paleoart, with depictions attempting to reconstruct entire prehistoric ecosystems.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins further popularized paleoart in the mid-19th century by sculpting life-sized models of dinosaurs for London’s Crystal Palace. However, many of these early depictions, heavily influenced by contemporary scientific beliefs, portrayed dinosaurs as slow, sprawling, reptilian giants. This perception persisted for decades until new discoveries reshaped our understanding of these ancient creatures.

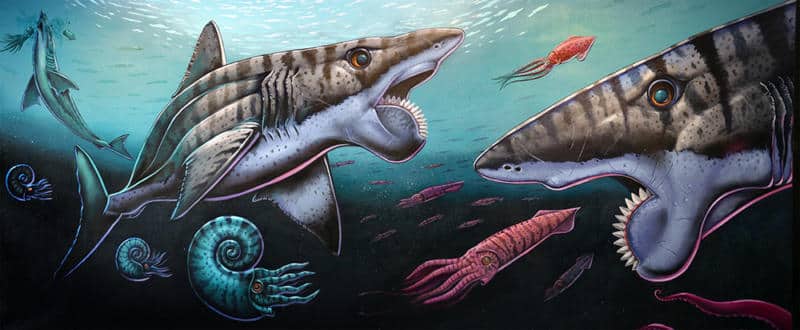

Ray Troll calls himself a “scientific surrealist,” blending meticulous scientific detail with whimsical humor in his art. A lifelong paleo enthusiast, Troll says, “I was basically born a paleo artist… one of the first things I remember drawing was a dinosaur.” His work spans from prehistory to the ocean’s depths, with a signature fascination for creatures like the ratfish—a deep-sea oddity he calls “a living fossil” that looks like “a visitor from another planet.”

Troll’s art is as much about education as expression. He collaborates with scientists to ensure accuracy, but always filters it through his imaginative lens. “If I can get you fascinated with what I’m fascinated in… maybe that fascination leads to caring about something,” he says. From T-shirts to full-scale museum exhibits, his work is playful, profound, and deeply personal.

The Dinosaur Renaissance: 20th Century Shifts

The 1960s and 1970s saw a dramatic shift in both paleontology and paleoart. John Ostrom’s discovery of Deinonychus challenged the notion of dinosaurs as sluggish reptiles, suggesting instead that they were active, dynamic creatures. Robert Bakker furthered this view, proposing that many dinosaurs were warm-blooded and bird-like in behavior. Paleoartists began reflecting these scientific changes in their work. Zdeněk Burian produced breathtakingly detailed prehistoric landscapes, while Rudolph Zallinger’s famous Age of Reptiles mural at Yale’s Peabody Museum captured the evolutionary timeline of dinosaurs. Though influential, Zallinger’s work still depicted dinosaurs as relatively static, a notion that would soon change with further scientific advances.

One of the most significant moments in paleoart history came with the release of Jurassic Park (1993). Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster film, based on Michael Crichton’s novel, introduced the public to dinosaurs depicted as fast, intelligent, and deadly hunters. The movie’s special effects were guided by paleoartists such as Mark Hallett, who ensured that the dinosaurs reflected the most current scientific knowledge available at the time.

While Jurassic Park was groundbreaking in its portrayal of dinosaurs as dynamic animals, it also took artistic liberties. The film’s Velociraptors, for instance, were significantly larger than their real-life counterparts, and the absence of feathers (despite mounting evidence suggesting some theropods were feathered) left an inaccurate but lasting impression on audiences.

Today, paleoart has reached new levels of accuracy thanks to collaborations between artists and paleontologists. Advances in fossil analysis, CT scanning, and biomechanical modeling have allowed for highly detailed reconstructions of prehistoric life.

Gregory S. Paul revolutionized the field by emphasizing skeletal accuracy and musculature in his dinosaur reconstructions. Meanwhile, paleoartists like Mark Witton and Emily Willoughby have embraced new discoveries, depicting dinosaurs with feathers and more bird-like postures.

Perhaps the most significant shift in modern paleoart is the emphasis on speculative but scientifically plausible depictions. The book All Yesterdays (2012) by Darren Naish, C. M. Kosemen, and John Conway encouraged artists to think beyond rigid scientific reconstructions, exploring soft tissues, behaviors, and environmental interactions that might not fossilize but could reasonably have existed.

Fair Feathered Friends

It is time for you to become a paleoartist! Using images from OMSI’s fossil collection, create your own rendering of what you think these prehistoric creatures looked like. Don’t be afraid to take artistic liberty or aim for scientific accuracy.

Look at the picture, and imagine what the animal looked like when it was alive. What size was it? Where would muscles go? What type of skin did the creature have? What did it smell like? Use your senses to imagine this creature during its lifetime.

Draw what you think the animal looked like when it was alive. Feel free to get creative with colors, textures, and interpretations. This is your vision of what a dinosaur looked like.

Use a variety of craft materials to create a habitat for your animal. What kind of environment did the animal live in? What is the animal doing? What other animals or plants live there?

Background on the Different Species

Oreodonts lived from the Middle Eocene through the end of the Miocene (from about 40 million to 5 million years ago). They were a type of animal called an “artiodactyl”, which is an even-toed hoofed mammal. Modern artiodactyls include animals like bison and bighorn sheep, both of which can be found in the Badlands today. With four toes, oreodonts also fit the description! In life, oreodonts likely looked like a mix between a camel, sheep, and pig. Their closest living relative is the camel, but they are very distantly related.

Oreodonts were herbivores, meaning that they ate plants like leaves and shoots. We know this partially because of the shape of their teeth – being flat and low, oreodont teeth were meant for chewing and grinding plants. Oreodonts likely lived together in herds as a protective measure against predators like nimravid. Some oreodonts, like Leptauchenia had large auditory bulla (casing for inner ear bones) which indicate that it may have had large ears and exceptional hearing.

Triceratops, meaning “three-horned face,” was a large herbivorous dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period, around 68 to 66 million years ago. Native to what is now North America, this quadrupedal dinosaur is distinguished by its massive skull, which could measure up to one meter wide, and featured a large bony frill along with three prominent facial horns. Triceratops could grow up to 30 feet in length and weigh around 12,000 pounds. Its frill and horns likely served multiple purposes including defense, mating displays, and species recognition. Although these features were useful in warding off predators such as Tyrannosaurus rex, fossil evidence suggests Triceratops lived mostly solitary lives rather than in herds.

Fossils of Triceratops have been found since 1889, offering extensive insight into its anatomy and behavior. Its beaked mouth and battery of shearing teeth were well-suited for chewing tough, fibrous vegetation like palm fronds. A notable fossil discovery revealed healed bite marks on a horn, suggesting it had survived an attack from a predator—likely a T. rex—indicating active use of its horns in defense. Triceratops remains one of the most iconic dinosaurs, frequently featured in museums, films, and books. Its unique features and dramatic predator-prey relationships continue to make it a focus of both scientific study and public fascination.

The American mastodon (Mammut americanum) was a large, herbivorous mammal that roamed North America during the Pleistocene Epoch, eventually going extinct around 13,000 years ago. Similar to modern elephants, mastodons had flexible trunks and large tusks, but they were generally smaller, with males reaching up to 10 feet tall and weighing up to 6 tons. They were distinct from their relatives, particularly in their teeth—mastodons had cone-shaped cusps on their molars, designed for chewing shrubs and tree parts, unlike the flat, ridged molars of mammoths. Fossils of these creatures are common across North America, and their remains have been found in places like California’s Rancho La Brea Tar Pits.

Mastodons inhabited forests and wetland areas, where they likely fed on vegetation near swamps. They used their large tusks to strip bark and possibly to compete for mates, with males typically larger than females. Despite their similarities to elephants, mastodons had different behaviors and ecological roles, especially in their feeding habits. Evidence of their presence includes well-preserved footprints, giving us insights into how these massive creatures moved across the landscape. While their extinction may have been influenced by factors such as climate change and human hunting, much about their lifestyle and decline remains under study.

Tyrannosaurus rex, often called T. rex, was one of the largest and most formidable carnivorous dinosaurs to ever walk the Earth. Living approximately 66 to 68 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period, T. rex inhabited what is now western North America. Its name, derived from Greek and Latin, means “king of the tyrant lizards.” This apex predator could reach lengths of up to 40 feet (12 meters) and weigh between 5.5 to 8 tons. T. rex possessed a massive skull with teeth over 6 inches long and jaws capable of exerting a bite force estimated between 7,868 to 12,814 pounds, allowing it to crush bone and consume large prey. Despite its size, T. rex had relatively short forelimbs with two clawed digits, the exact function of which remains a subject of scientific debate. Recent studies suggest these limbs may have been used for grasping mates or assisting in rising from a prone position.

Fossil evidence indicates that T. rex had a keen sense of smell, aided by large olfactory bulbs in its brain, and forward-facing eyes that provided binocular vision for depth perception. While it was not a fast runner, estimated at speeds up to 12 miles per hour, its strength and hunting strategies compensated for its lack of speed. T. rex likely preyed upon other large dinosaurs and scavenged carcasses, exhibiting both predatory and opportunistic feeding behaviors. Growth studies suggest T. rex reached its full size in less than 20 years, with some individuals living up to 28 years. The species went extinct around 66 million years ago during the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, likely due to a combination of volcanic activity, climate changes, and an asteroid impact.

What’s the Science?

Paleontology is the science of studying ancient life through fossils—remains or traces of animals and plants that lived millions of years ago. This fascinating field has helped us learn about creatures like dinosaurs, ancient plants, and even the earliest life forms on Earth. In this section, we’ll take a look at the history of paleontology, how it began, and the important role that paleoart (art that recreates ancient life) has played in getting people excited about dinosaurs!

The first discoveries of fossils happened long before paleontology was even considered a science. Ancient people saw strange bones and shells in the ground, but they didn’t know what they were. Many thought they belonged to giants or mythical creatures. Some famous thinkers, like Aristotle, even wrote about fossils, but they didn’t quite understand that these were the remains of long-lost creatures.

It wasn’t until the 1600s and 1700s that scientists started to really study fossils. In 1667, Nicolas Steno, a scientist from Denmark, began to notice that fossils were often found in layers of rocks, showing that Earth’s surface had changed over time. This idea helped scientists understand that the world was much older than they had thought. Later, in the 1700s, a French scientist named Georges Cuvier made an important discovery: some animals whose fossils were found no longer existed! This was the beginning of the idea of extinction, which changed the way people thought about life on Earth.

The 1800s were an exciting time for paleontology because it was the century when dinosaurs were first discovered! In 1824, an English scientist named William Buckland described the first dinosaur fossil—a meat-eating dinosaur called Megalosaurus. Around the same time, a scientist named Richard Owen coined the term “dinosaur,” meaning “terrible lizard.” This was the beginning of our fascination with these huge, strange creatures that lived millions of years ago.

As more fossils were discovered, including those of the massive Triceratops and the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex, people started to realize that dinosaurs were real creatures that once roamed the Earth. The fascination with dinosaurs grew, and paleontologists continued to find amazing new fossils.

Paleontology has continued to evolve with new discoveries and technology. Today, scientists use advanced tools like CT scans and 3D imaging to study fossils in ways that were never possible before. For example, paleontologists have discovered feathered dinosaurs and other surprising facts about ancient animals that were once thought to be just scaly reptiles.

Thanks to the work of paleontologists and paleoartists, dinosaurs continue to capture our imaginations. They appear in books, movies like Jurassic Park, and even in video games. The images that paleoartists create—along with the discoveries of real fossils—help us learn more about these ancient creatures and keep the wonder of paleontology alive for future generations.