Frigid Forestry

The Boreal Forest, often called the “lungs of the planet,” is a vast and vital ecosystem stretching across the Northern Hemisphere. It plays a crucial role in regulating the global climate by storing carbon, purifying air and water, and providing a habitat for countless plant and animal species. However, this forest faces growing threats from industrial activities, climate change, and habitat fragmentation, making conservation efforts more critical than ever.

Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (ITEK) is essential to these conservation strategies. Rooted in generations of lived experience and cultural connection to the land, ITEK offers invaluable insights into sustainable resource management, biodiversity, and ecosystem health. By blending ITEK with scientific approaches, conservation initiatives become more holistic, fostering collaboration and ensuring the protection of the Boreal Forest for future generations.

What is a Boreal Forest?

Boreal forests, also known as the taiga biome, are vast ecosystems that stretch across the northern regions of the world, including parts of Alaska. In the United States, they span from Alaska’s Brooks Range to the Kenai Peninsula, covering 60-70% of Alaska’s forested land. These forests experience long, harsh winters, with temperatures remaining below freezing for 6-8 months each year. Only cold-tolerant conifer species, like black and white spruce, thrive in this environment. However, rising temperatures and increased wildfire frequency are shifting the landscape. Older spruce forests are being replaced by deciduous trees like birch and aspen. Additionally, the warming climate is intensifying the risk of wildfires, which may release significant carbon stored in trees and thawing permafrost. Invasive species such as earthworms, mountain pine beetles, and Siberian moths are also becoming more prevalent, further threatening the forest’s stability. These combined factors may soon turn the boreal forest from a carbon sink into a carbon source, exacerbating climate change. Boreal ecosystems are not only vital for the survival of local wildlife, but they also provide essential services for the planet, including carbon storage and oxygen production. In particular, species like the Roosevelt elk and the Northern Pacific tree frog play key roles in maintaining the health and balance of these forests.

Knowing Nature: Stories of the Boreal Forrest is an exhibited at OMSI between January 25-July 6, 2025. This beautiful exhibit thoughtfully combines interactive experiences, stunning media, first-person stories, and commissioned objects to immerse visitors in the boreal biome. Watch the video below to see the fun in-depth experiences are!

Ecology Working Together

The Roosevelt elk, found in the boreal forests of North America, is a particularly important herbivore. These large animals help manage plant growth by grazing on grasses and shrubs. This grazing helps to maintain a diverse plant community, preventing any one species from becoming too dominant. By feeding on certain plants, elk also help create open spaces that allow new vegetation to grow, supporting the overall health of the forest. Additionally, Roosevelt elk are a crucial food source for predators like wolves and bears, making them a central part of the food web in the boreal forest.

Similarly, the Northern Pacific tree frog, though much smaller in size, plays an essential role in the boreal forest ecosystem. These frogs thrive in moist areas under the dense canopy of trees, where they feed on insects like mosquitoes and flies. By controlling insect populations, the tree frog helps prevent these pests from overwhelming the forest. Additionally, tree frogs themselves are an important food source for birds, reptiles, and other predators, making them a key component of the forest’s food chain

Can’t Sweat the ITEK-nique

Indigenous and Traditional Ecological Knowledge, or ITEK, refers to the deep-rooted understanding of the environment passed down through generations by Indigenous peoples and local communities. It is built through direct experiences with nature and includes knowledge about plants, animals, landscapes, and seasonal changes. This wisdom is not static; it evolves as communities continue to observe and adapt to their surroundings. ITEK involves the relationships between living beings, natural phenomena, and the ways these interactions shape the lifeways of Indigenous people, including practices like hunting, fishing, and forestry. Books such as Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass elaborate on the roles of Indigenous knowledge as an alternative or complementary approach to Western/European mainstream scientific was of thinking and stewardship.

Indigenous Stewardship

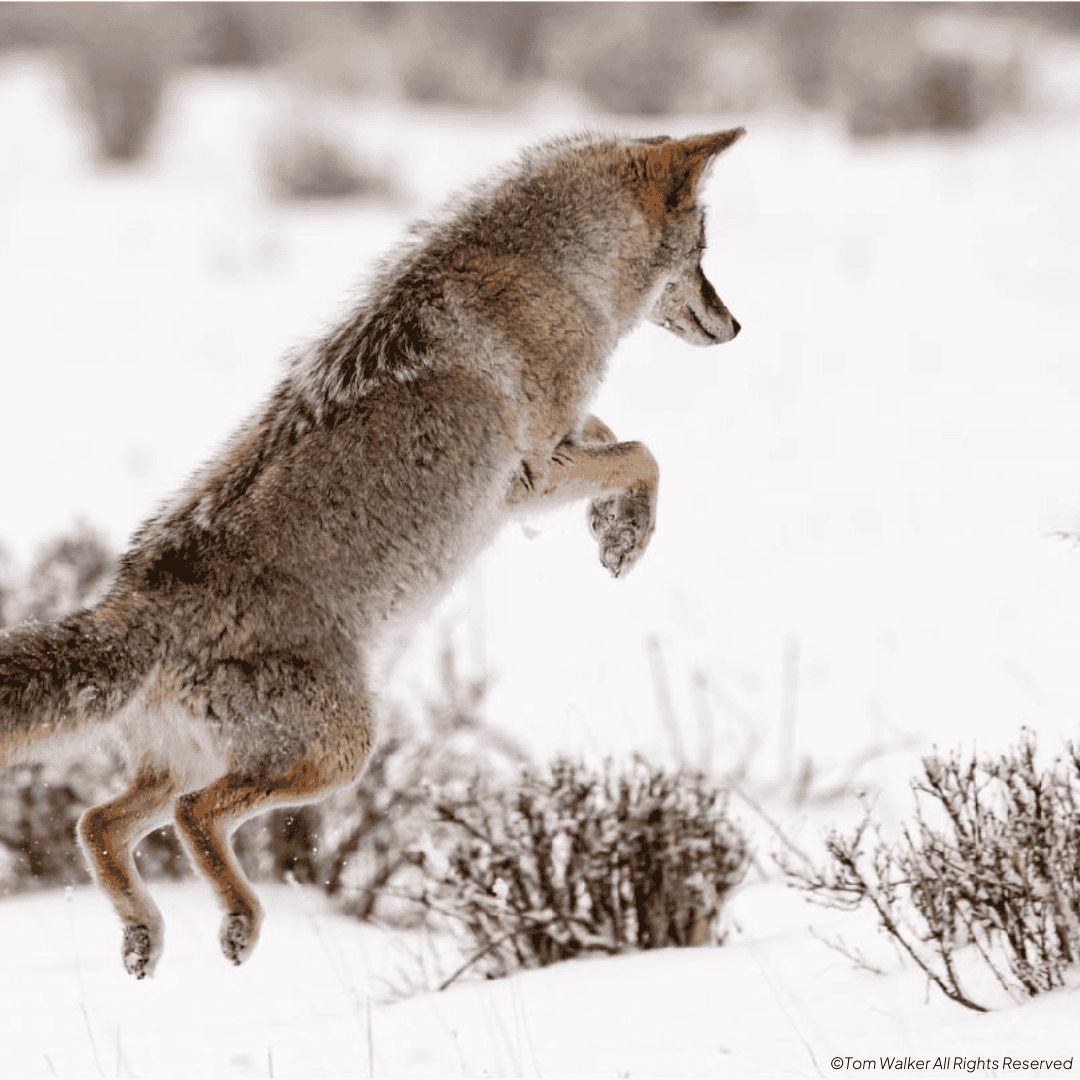

Indigenous peoples have long practiced sustainable management of the boreal forest, using techniques like selective hunting and fire management to maintain healthy ecosystems. Selective hunting involves harvesting only certain animals at specific times, ensuring that wildlife populations remain balanced and healthy. This practice prevents overhunting and helps maintain the stability of the food web.

Fire management is another traditional technique used by Indigenous peoples to manage the forest. Controlled burns, which mimic natural fire cycles, help clear out dead vegetation, promote the growth of new plants, and maintain habitats for wildlife. These fires also reduce the risk of larger, more destructive wildfires, helping to protect the forest and its inhabitants.

Leafy Reflections

When in nature it is important to reflect on its abundance and your connection to the land you occupy. Use the OMSI field guide to go out into your local wilderness and reflect on the following prompts.

OMSI Field Notebook

- Look around and imagine the forest as a living, multi-story home. The canopy high above, the understory of shrubs and young trees, the forest floor full of ferns and fungi, and the roots below — each layer has its own residents! Boreal forests often have fewer layers because of the harsh climate, but here in the Pacific Northwest, biodiversity flourishes. What plants or animals can you spot in each layer? How do you think they depend on each other to keep this ecosystem healthy?

- Close your eyes and listen — can you hear the trickling of a stream or the drip of water from the leaves? The Pacific Northwest’s forests are shaped by rain and mist, while boreal forests experience long, dry winters. How does all this water move through the forest? Imagine you’re a drop of rain: how might you travel from the sky, down a leaf, into the soil, and eventually out to the ocean? Why is clean water important for both the plants and animals here — and for us, too?

- Some of the trees in this forest might be hundreds of years old, standing tall as living witnesses to history. In boreal forests, trees tend to grow more slowly and don’t often live as long due to the cold. Why do you think these Pacific Northwest trees grow so large and live so long? If you could talk to one of these old trees, what story might it tell about the changes it’s seen? How can we help protect these ancient giants for future generations?

- A healthy forest needs caretakers — just like a garden! Both boreal and temperate rainforests face threats like logging, climate change, and invasive species. What small actions can you take to help protect this forest, like staying on trails, not picking plants, or learning about endangered species? How might sharing what you’ve learned today inspire others to care for these wild places? What does being a “forest steward” mean to you?

What’s the Story?

Forests are more than just collections of trees — they are living landscapes filled with stories, traditions, and deep-rooted relationships between people and nature. For Indigenous communities across the Boreal Forest, the land is not only a source of resources but also a part of their identity and culture.

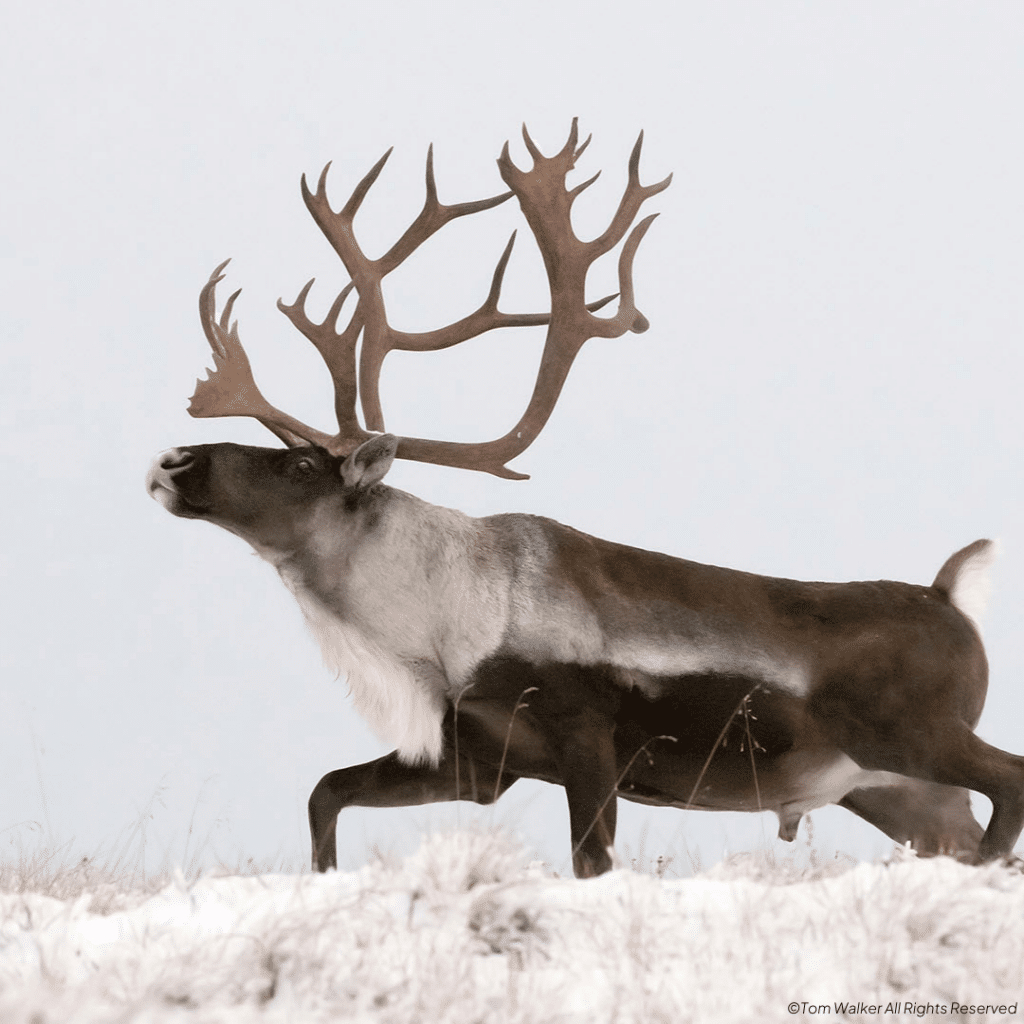

Indigenous nations, such as the Łutsël K’e Dene First Nation, the Dehcho First Nations, and the Sayisi Dene First Nation, have long been stewards of these lands. These communities protect vast areas of forest by combining traditional knowledge with modern conservation techniques. For example, the Thaidene Nëné protected area, co-managed by the Łutsël K’e Dene First Nation, covers 6.5 million acres of boreal forest, safeguarding habitats for caribou, moose, and countless bird species.

Indigenous stories often reflect this interconnectedness. These stories teach younger generations about the natural cycles of the forest — the movement of animals, the changing of the seasons, and the role of fire and water. Dehcho elder Jonas Antoine once described their protected land, Edéhzhíe, as “a gift for the future,” emphasizing that caring for the land ensures it will continue to support life for generations to come.

Through cultural protocols, Indigenous laws, and spiritual practices, these communities view themselves not as owners of the land, but as its caretakers. This belief underscores the important message: “We take care of the land, and the land takes care of us.”